What is Narrow Money?

Understanding money supply requires familiarity with various types of money. Today, we’ll focus on U.S. definitions and the supply of U.S. dollars. At the most stringent end of money supply measures lies narrow money, known as M0. It encompasses physical currency in circulation and bank-held cash reserves, often termed the monetary base.

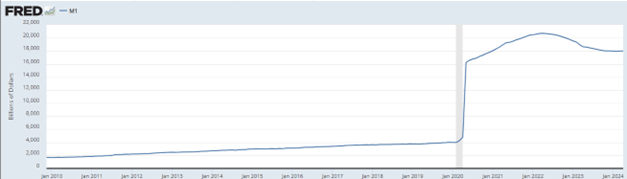

Moving to the next category, we encounter M1, which includes all elements of M0 along with demand deposits and traveler’s checks. Demand deposits are liquid funds in bank accounts available for immediate withdrawal by customers.

You might wonder if banks actually keep all this cash ready for withdrawal. The answer is no. This money is digitally recorded in the fractional reserve system. Banks utilize risk assessment to determine necessary cash reserves across branches, beyond what’s physically stored.

In essence, M1 comprises digital funds available for withdrawal, including traveler’s checks, marking it as narrow money.

What is Broad Money?

Broad money encompasses M1 and beyond, known as M2 and M3 in the U.S.

M2 consists of M1 plus money market savings, small time deposits under $100,000, and shares in money market mutual funds. Essentially, M2 covers all liquid and some less liquid assets.

Further expanding,

[...]

Creating freedom through Crypto as a Community